A funny thing happened in the 1970s and 1980s.

As horror films got more violent and we became more voyeuristic as an audience, many of us started to root for the killers over the victims. And suffice it to say, looking around at our modern media landscape, it’s plain to see that the “killer as main character” story has definitely become a permanent thing in our podcasts, shows, and movies.

There are many reasons for this that we’ll get into. But it didn’t come out of nowhere...

One of the most notable proto-serial-killer films is Fritz Lang’s M (1931). The story follows a group of criminals who band together to hunt down a child murderer who keeps eluding the cops. It’s a fantastic, gritty, beautifully shot film, especially that powerhouse of an ending where the criminals finally catch their prey and put him on “trial.” But the main difference from what came later is that we were never expected to “understand” Peter Lorre’s Hans Beckert here.

No, it wasn’t until three decades had passed that pop culture became obsessed with putting us inside the heads of killers. And that trend began with a boy and his mother.

Psycho (1960)

A Dracula story

For the first half of Psycho, Marion Crane is our protagonist. We follow her from frame one as she meets with her lover, steals money from her boss, and flees the city. In short, we find ourselves in a crime thriller.

Marion is a literal thief on the lam – she even has a run-in with the law - and we are intrigued by the central question of the film at this juncture: “Will she get away with it?”

But then, Marion pulls over for a fateful stay at the Bates Motel, she takes a shower, and “Mother” kills her.

Suddenly, Mother’s son Norman Bates becomes our protagonist, and the central question becomes, “Will he get away with it?”

And just like that, we find ourselves in a Gothic Horror film… one where the horror is not supernatural but is hidden under the surface of Americana imagery, taking us into the secret dysfunctional darkness of the American nuclear family as well as the dark duality of the American psyche.

Visually, we are shown this distinction via the dichotomy of the Bates Motel in the foreground and the Victorian-style Bates house atop a hill in the background – an ancestral home of dark secrets leering over American modernity.

With that in mind, it is no coincidence that the Bates residence resembles a prototypical haunted house from Gothic cinema since Norman is indeed haunted by his mother… resulting in grave consequences for anyone who crosses his path.

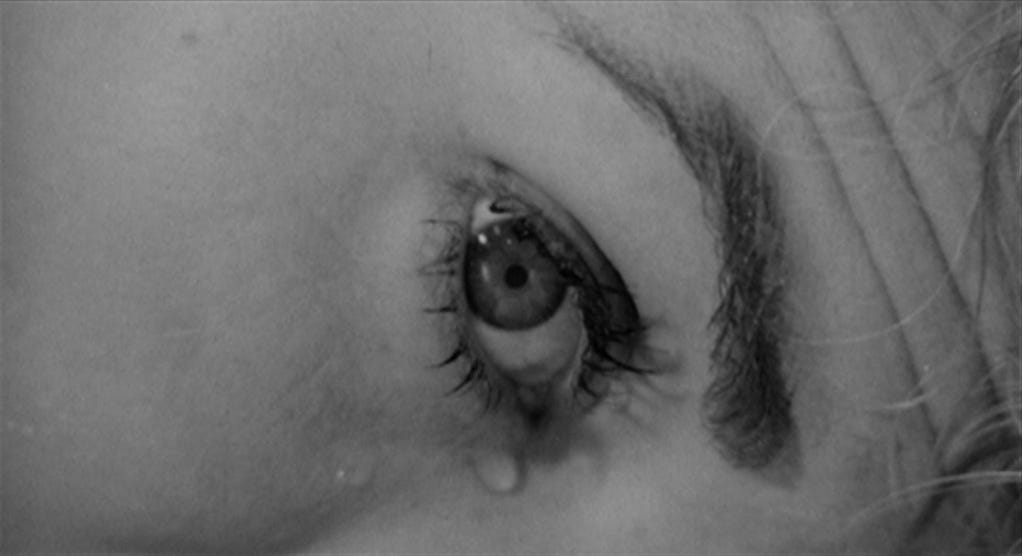

Much has been said about the ingenuity of Psycho’s infamous shower sequence (enough can’t be said about it, frankly). But the most important thing as far as engendering audience sympathy goes is that it shows us just how brutal Mother is.

Those quick, dramatic camera angles, brilliantly cut together by editor George Tomasini in such a way as to show us every single stab in impressionistic flashes, heightened by Bernard Herrmann’s wonderfully abrasive score and Janet Leigh’s heartbreaking performance… it feels visceral and shocking, as if Mother really is taking out her repressed demons on poor Marion.

And this brutality is the key to keeping us on Norman’s side later on; after all, he didn’t kill Marion in such a fashion, his monstrous mother did.

The first time we realize that Norman has our complete allegiance is when he attempts to get rid of Marion’s body. He puts her in the trunk of her car, he pushes the car into the swamp, the car starts to sink… and then it stops.

We instantly fear that Norman will get caught covering up his mother’s crime, but then we sigh in relief as the sinking resumes and the car disappears.

And that’s it, that’s the moment right there: Alfred Hitchcock, master director that he is, and Joseph Stefano, master screenwriter that he is, have aligned our empathy, however unwittingly, with Marion's killer.

It’s the “unwitting” part that rings especially true. Yes, our sympathies shift from Marion to Norman after Marion is gone, but it’s mostly because we don’t have a choice. We are stuck with Norman for the rest of the movie, as it were, and we are subconsciously seeking a reason to connect with him as our new hero.

It’s not our fault – remember, at this point, we don’t know the truth about Mother* yet, and we think she’s a monster.

*This movie had so many controversial qualities that were thrust into the spotlight - it was blasted for being the first film in history to show a toilet flushing onscreen, among other things – yet Janet Leigh’s early exit and the truth about Mother were never leaked pre-release, which made them true surprises. That’s pretty crazy when you think about it, given today’s spoiler culture.

All we’ve seen (or heard) of Mother thus far is that she is an abusive crone who seems to have terrorized her son all his life, to the point where she has broken him as an adult. And that’s the “in” we need to be on Norman’s side, in a lesser evil kind of way.

We may not pity Norman, but we at least understand why he is who he is. Consequently, because of their abusive relationship, we assume that Norman will do battle with Mother and expose her in the end.

Technically, that does indeed happen… just not in the way we imagined.

Much in the same way that Dracula and Frankenstein set the template for every horror story, I would say Norman Bates set the template for every modern slasher villain.

The biggest Freudian elephant in the room, of course, is that most slashers are driven by sexuality - gotta get those impure teens – thus following in Norman’s footsteps. After all, voyeuristically peeping in on Marion is what flared up Norman’s repressed sexual feelings, which triggered Mother’s rampage.

And the second core attribute that has been carried over to today, especially in our true-crime-obsessed culture, is that Norman’s story was rooted in real-life horrors.

It is no secret that many of the most iconic horror films of all time used true events as source material.

For instance, Psycho, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974), and The Silence of the Lambs (1991) all borrowed from the Ed Gein murders to varying degrees. David Fincher’s Zodiac (2007) obviously followed the true-life manhunt for the Zodiac killer. Even The Exorcist borrowed from a supposed non-fiction book source, wherein a priest performs an exorcism on a young farm boy.

However, while the “real” inspirations behind these films are certainly scary on their own, those sources are just the underpinning. It won’t mean anything if the kills look fake, the lighting is off, and the jump scare is just a loud noise with no invention behind it.

Meaning, it all depends on the filmmakers’ execution (remember that?) as far as being scary on film goes.

The storytellers must first tap into our primal fears - that’s the “idea” part, the “concept” part. Then they must find the best places to put the cameras, the optimal ways to block the scenes, the most effective ways to orchestrate the actual scares, and the most imaginative ways to reach into our collective psyches and bring it all to life.

Take director Tobe Hooper’s The Texas Chain Saw Massacre. That film works because it just feels real. It looks grimy and uncomfortable in every frame, and as a result, a true sense of unease permeates the entire thing. And the way cinematographer Daniel Pearl’s camera captures the horror – either in shaky close-ups or in naturalistically-composed wide shots – undeniably adds to the feeling of actually “being there.” It’s practically a documentary.

I’ll never forget the first time I saw this one. I was in high school, and we were at a friend’s house, watching it in the dark. And when Leatherface* bursts out of the meat locker with the hammer – you know the scene – our friend, who was lying on the floor, sat up like a rocket. We could only see him in silhouette, and his hair was standing straight up like Sonic the Hedgehog. He paused the movie and just stared at the TV for a good 30 seconds before softly saying, “Ok,” and pressing play again. Getting a reaction like that takes an instinctive talent, and that’s what makes it so hard to capture.

*Of all the modern slasher villains, Leatherface probably comes the closest to being a Frankenstein figure, but I would still classify TCM as a Dracula story because he doesn’t elicit any sympathy at all. Just a big ol’ scary lug!

With the obvious caveat that the early horror films we’ve discussed thus far should be admired as iconic first steps, the psychologically realistic modern filmmaking techniques ushered in by films like Texas Chain Saw Massacre helped us suspend our disbelief much more effectively as time went on, which is absolutely essential in horror films.

If we are to be scared, our minds must be temporarily tricked into thinking that what we are seeing is “real.” Even when we’re dealing with escapism.

So, what do those real primal fears add up to in the context of slasher films, which often don’t have realistic plots? It all goes back to Norman Bates, of course, and that voyeuristic link between sex and violence.

Unknowingly being watched and stalked at our most (literally) naked and vulnerable state by a predatory force whose hidden visage puts an insurmountable distance between us and safety is pretty scary.

There’s also the fear of God that’s been hammered into us by a society governed by moral panic, always shouting about how we will be punished if we indulge in our vices. It’s all hardcoded stuff that results in effective buttons to push.

Oh, and the idea of watching everyone we care about being systematically murdered during fun, wholesome holidays wherein we constantly have our guard down seems to hit the fear spot too…

First, a shout-out to 1974’s way-too-often overlooked Black Christmas!

Creepy obscene phone calls, eerie silences, well-staged murders, a formidable unseen killer, interesting camera angles, a bleak ending, and an overall nihilistic tone make this the first true (and truly scary) slasher film.

It’s also worth taking a moment to acknowledge filmmaker Bob Clark’s amazingly varied career. Not only did he direct Black Christmas (and Porky’s!), but he also directed A Christmas Story nearly a decade later. It’s not every day one can say they made two perennial holiday classics at completely different ends of the genre spectrum!

But as good as Black Christmas is, the slasher movie murder spree was truly started by a ghostly Shape in a white mask.

Halloween (1978)

A Dracula story

As far as the impact of Halloween goes, we can also start with the “look” of things.

Much like Tobe Hooper did with The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, director John Carpenter was going for a “naturalistic” look here. He clearly wanted the town of Haddonfield to feel like any small town, which makes it instinctively terrifying because it could be your town.

And that wholly taps into one of the primal fears we’ve touched on plenty already: the invasion of our safe spaces, our homes, by a hostile force.

Then there’s the blocking and the framing. Right away, we have the innovative “POV Kill,” which puts us in Michael Myers’ mindset* from the beginning of the film. What makes this scene so effective is that we feel as if we are performing that murder, and yet we can do nothing to “stop ourselves” because we are just sitting in front of a screen.

Moreover, Carpenter revisits Michael’s POV at several points throughout the film, and this only further makes us confront the realization that we can’t stop our darkest urges because they are intrinsically anchored to our voyeuristic natures.

I wouldn’t go so far as to say we relate to Michael or anything. But it’s not like we are going to turn off the movie - we can’t help but want to watch. We love naked people and violence, what can I say?

*What has always been interesting about Michael Myers as a character is that we see him commit his first murder as a child, all primal id and debased desires, and he remains stuck in that mindset for the rest of his life. A cautionary arrested development metaphor if there ever was one.

On the flip side, Halloween also makes us feel like victims.

Carpenter gives us several stalking scenes where Michael Myers just stands there in plain view, and to be able to make something feel so damn creepy in the broad light of day like that is a truly admirable feat.

Carpenter accomplishes this creepiness by always showing Michael partially obscured by something, or by lingering on him for just seconds at a time - he’s always at the edge of our vision, like a half-forgotten nightmare.

Furthermore, Michael’s eerie visage is always juxtaposed with mundane everyday sights like laundry clotheslines and sidewalk hedges, which once again underscores the fear of some unearthly, dangerous thing coming into our lair.

Light and shadow are manipulated by cinematographer Dean Cundey to grand effect here – we truly feel as if we are in the same room as Michael Myers whenever he executes his kills or attacks our protagonist Laurie Strode.

This taps into yet another primal nightmare: the fear of being hunted by something unstoppable. And the fact that Halloween so effectively makes us feel like both predator and prey is what makes it so iconic.

And that brings me to The Final Girl trope.

This term is used to describe how, primarily in slasher movies, all the victims are picked off one by one until only a solitary female character is left to go head-to-head with the killer. (Watch the 2015 film The Final Girls, which does a highly enjoyable Back to the Future riff on this trope!)

We often point to Halloween’s Laurie Strode as the first true Final Girl - long live Jamie Lee Curtis! - but it is not solely because she is the last one standing. It is also because she is the “purest” among Michael Myers’ victims. (Note how she doesn’t have sex in the film, and the other characters tease her about it).

This came to be the defining “moral panic” attribute of the trope – the Final Girl is usually innocent and “good,” which means that she does not give in to carnal pleasure. Thematically, that’s why she prevails.

However, to further complicate things from a Freudian perspective, Laurie uses phallic symbols, such as a straightened coat hanger, to “penetrate” Michael Myers as she is defending herself from him. This symbolizes that, in fighting back, Laurie subverts the very thing Michael is drawn to when he picks his prey: sexuality.

Aaand that brings us to the hypersexualized, hyperviolent 1980s!

After the success of Halloween, the slasher film erupted into a horror genre of its own. And it seemed like the farther away we had gotten from the Hays Code, the more that sex and violence had gone off the charts. (Some of the things that were rated PG back then would turn your hair white today, which is why you had movies like Gremlins leading to the creation of the PG-13 rating.)

At the same time, something even more interesting happened in the years after TCM and Halloween: As we moved along the slasher film timeline, things started to get less “real,” especially in terms of tone and concept.

Maybe audiences didn’t want to be scared in quite the same ways anymore, given the exhausted zeitgeist of the time – we were still processing Vietnam, and horrific reports of rising crime were running rampant all over the news.

This meant that the appetite for realism in our horror films had regressed; we wanted to become as detached as possible from our escapist entertainment. We had resorted to our voyeuristic “let’s watch people get killed” gladiator arena days, with the added bonus of it not being real so we didn’t have to feel guilty.

We had embraced a new kind of catharsis.

Desensitization kicked in, which kicked characterization out – most slasher screenplays stopped caring about their characters because it was assumed that’s not what the audience was there for. After all, it’s much easier to cheer on the killer when the horny teens he’s after are vacuous and empty.

Fresh variations were added as well, such as making the killer supernatural in order to push our minds even farther away from thinking about our everyday murderers. Yet these fantastical tweaks were often grafted onto the same slasher codes and conventions as before – a tantalizing mix of new and old.

Ultimately, the emphasis was placed on the villains; fun, blood-drenched scares and over-the-top nudity became the priority for many horror movies. It was just like when we switched allegiances from the victim to the victimizer in Psycho mid-film, only it was spread across the whole genre.

And this meant that the killers became the stars of the show.

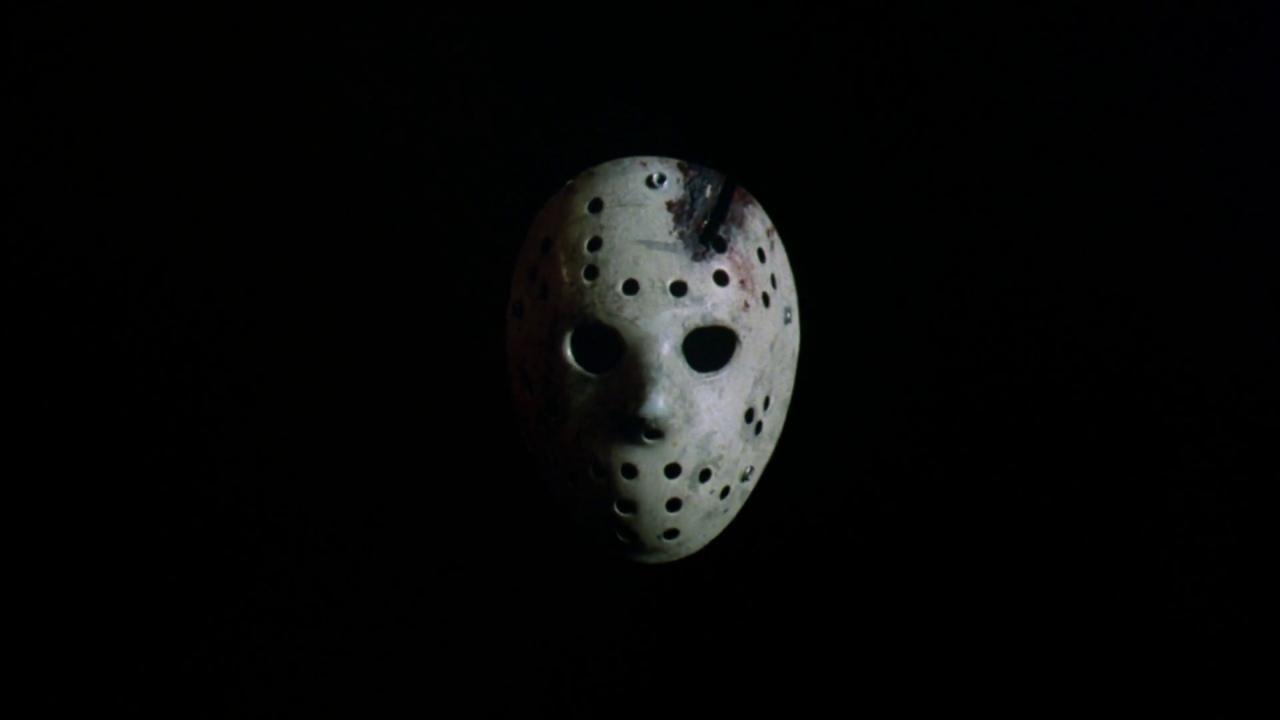

Another iconic slasher star named Jason Voorhees was unleashed unto the world in 1980’s Friday the 13th… although, as fans know, Jason’s mother was actually the murderous star of part one. Yes, the twist of who the killer was amounted to Mother in reverse, but this wasn’t the only Psycho inspiration.

That first Friday the 13th film gleefully expanded on the voyeuristic formula its landmark predecessor had established, albeit with a higher body count: repressed sex punishment, inventive kills, a slasher dressed up in a memorable fashion, check.

That said, Jason also followed in Michael Myers’ footsteps in that both films ended with a decidedly supernatural declarative statement: Our guy is not of this world, which means he can’t be killed. In fact, as both series went on, Michael and Jason essentially became more and more fanciful, always returning from the grave with some added mythology to their backstories.

And somewhere along the way, they opened the door for the ultimate supernatural slasher…

A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984)

A Dracula story (of course)

In keeping with some of his slasher predecessors, the “urban legend” nature of Freddy Kruger also had roots in true events.

Writer-director Wes Craven found inspiration for this film within several Los Angeles Times articles about Hmong war refugees who had fled to the United States and died in their sleep soon after suffering disturbing nightmares.

Craven then took that terrifying idea and asked, “What if an actual entity was behind that? What if you could get killed in your dreams?”

It is an all-time great idea for a horror movie, one where the most basic human need becomes our worst enemy – a concept that ended up doing to sleeping what Jaws had done to beachgoing. (That’s why Freddy has always been my favorite of the “modern monsters.”)

Simply put, Nightmare’s premise taps into every allegorical, intimate, and voyeuristic aspect of the horror genre we’ve discussed thus far by covering these three tenets:

Our fears will haunt our subconscious until we vanquish them.

The bogeyman will catch us while we are asleep, which is when we are at our most vulnerable.

We can’t turn away, no matter how nightmarish it gets, because we are fascinated by sex and death, the two extremes of life.

It’s also one of those rare cases where budget limitations actually helped strengthen such a kickass concept.

In short, there was no money to build an elaborate nocturnal dream world of demonic frights from a production design standpoint, so Craven and his team had to make do with what they had.

And they made it work because they stuck to the “make it feel real” aesthetic that had elevated the best of Nightmare’s predecessors.

We notice it from the start: The film opens in a dark, steamy boiler room lit with reddish accent lights - a real location and not a set - so right away it just looks and feels nightmarish. And the rest of the film keeps that aesthetic going.

Jacques Haitkin’s cinematography is the opposite of glossy and brightly lit, ensuring that the tension is never sucked away. As a result, the film’s real settings never come across like movie sets, feeling instead like a modern, minimalist version of German Expressionism that captures the relatable psychological state of fighting to stay awake because you don’t want to face your deadly dreams.

Consequently, as the characters become sleep-deprived and the dream world begins to bleed into the real world, Craven uses the nooks and crannies and shadows of his locations to build and execute scares in incredibly inventive ways.

The set pieces are so clever here, from the bathtub scene to the ceiling kill to the blood-geyser bed to the surprise Jason-like ending.

And the fact that it all relentlessly unfolds in real places like bedrooms, neighborhood streets, and school hallways only adds to the dreadful atmosphere, expertly tied to the idea of nightmares invading our everyday lives.

It's that intimacy thing again - the more personal the threat, the deeper the fear.

Another key trait that Nightmare shares with the best of its predecessors is that it took the time to endear you to its characters. This stood out in 1984 because, again, many slashers had already reached the “kills over characters” stage.

Nancy – like Laurie in Halloween - is a great Final Girl, empathetic and strong all at once. The rooting factor only grows as we see that she is surrounded by a loving family and a group of friends who just seem like regular kids; we don’t want any of them to succumb to the hellish threat.

And then there’s Freddy himself. His frightening look – the charred face, the grungy hat and sweater, the rusty finger knives – melds perfectly with Robert Englund’s immortal performance. Simply an icon.

And just like Michael Myers in Halloween, Freddy is an intimidating force of nature here because he's not introduced in full right away; we never see him clearly till the end, so there's a true sense of buildup and mystery around him.

Again, it all fits so perfectly into the waking nightmare concept. Craven and his team designed the ideal mythic figure to embody the unknowable fears that plague our psyches… especially in our dreams.

The popularity of these slasher rockstars like Freddy, Jason, Michael Myers, and Leatherface, along with later ones like Chucky from Child’s Play and Pinhead from Hellraiser, ballooned to monumental heights in the 1980s – far greater than we had ever seen in the horror genre. There were countless cinematic imitators, Halloween costumes, songs on the radio, TV shows, video games, you name it.

And all of that makes me wonder if we will ever see a new horror icon again.

The last one to make a mark was probably Ghostface from 1996’s Scream. There have been a few other candidates in the ensuing years, such as Jigsaw from Saw, but he doesn’t really hit the mark in the same way because he’s just a dude in regular clothes without a legendary look. Plus, he’s more “morally questionable” than evil.

I personally love the Babadook from The Babadook and Sam the Pumpkin Kid from Trick ‘r Treat, but I also recognize that they are quite niche.

There’s Anabelle and The Nun from The Conjuring series, but I think the set pieces are the drivers of those movies, not the monsters (I love the “clap-clap” sequence from the first film, for example).

Here’s a thought, though: The mainline Conjuring films are centered around the adventures of paranormal investigators Ed and Lorraine Warren, characters we care about and who care about each other. They’re not just fodder, and maybe that’s the key.

Maybe we miss protagonists like Marion Crane.

Since many wannabe slasher films tend to use the same ideas over and over without trying anything new in the scare department, without bothering to give us a unique villain/mythology/hook, and without giving us characters to invest in, I think a lot of horror fans have mostly turned elsewhere for their scares.

And that brings me back to the original thought that started this piece – when you consider today’s serial killer fad, it seems like voyeurism might have come full circle. People have gone back to wanting to be scared in realistic ways.

Nowadays, the grislier the crime, the more that true crime aficionados want to know about it - it certainly feels as if people are more interested in getting inside the heads of killers than at any other time in history. Pondering what could drive us to commit atrocities against each other is perhaps the last unsolved mystery we have. Nothing is scarier than real life, I guess.

That’s voyeurism for you… we can’t help but want to watch.