As the world careened into the 1960s and 1970s, entertainment started to catch up to the anti-establishment counterculture that was overtaking society. As a result, horror films paradoxically seemed to get more intimate because they were allowed to become more visceral.

Meaning, the kills and the violence started to hurt more because they were coming at us with less filters. And these ideas and visuals that we’d never seen brought together in such a way before were being thrown into our faces via the wonderment of exploitation!

Exploitation films are low-budget thrill rides that rely on risqué subject matter (which absolutely means amped-up sex and violence) to help them grab people’s attention in the face of little to no studio backing.

This sensationalized form of filmmaking can usually be found in the action, crime, and horror genres since those are where the audience’s desire for escapist entertainment can be most easily exploited.

It’s a “we know what the masses want, and oh, BOY, are we going to give it to them” kind of ethos.

An interesting development to note is that the exploitation movement exploded (in some cases literally) onto the screen after the Hays Production Code went away, which meant that low-budget horror filmmakers dove into these films with abandon. It’s as if they had oodles of restrained violence and sex bottled up inside them after years of censorship, and they were finally able to release them in cathartic glee.

In short, from these days onward, horror movies just hit harder because horror filmmakers were able to go places they couldn’t go to before.

It's like they’d riiisen from the deeead…

Night of the Living Dead (1968)

A Frankenstein story

Night of the Living Dead was going to be made on the cheap, so director George Romero knew that he would need to compensate for his lack of resources with an abundance of shocking imagery. As such, he set out to show zombies onscreen as they had never been seen before… in all their cannibalistic, gory glory.

Put another way, Night of the Living Dead is chockful of scenes that would never have passed muster under the Hays Code. One image that sticks out right away (mostly because it can also be seen on the film’s poster) is the naked female zombie who shambles up to the farmhouse alongside her clothed brethren.

In America, that shot would’ve been unheard of just a few years before; in fact, since we have such a weird relationship with sex and violence in this country, I’d bet that more people were freaked out about the naked zombie simply wandering around than the clothed zombies devouring human intestines in close-up.

Another scene that sticks out is when the little girl turns into a zombie. Again, this scene is just filled with layers of “unheard of.” For starters, putting a child in peril onscreen is still considered to be taboo today, let alone back then. Then there’s the fact that the little zombie girl was shown murdering her parents – she eats her father and stabs her mother to death with a spade, in graphic detail.

Not only was this meant to be a visually disturbing scene in a visceral sense, but it also functions as a metaphorical “murder” of the societal repression we’d been subjected to for decades.

Symbolically, the “nuclear family” is “dissolved” here, and since the entire operating theme of society revolves around the “moral protection” of the family unit, this scene shows us that when things break down, human beings will break apart.

When we take such themes into consideration, it goes without saying that Romero had more on his mind than just exploitation.

Night of the Living Dead is a horror film with something to say – in this case, it offers up sobering commentary about the dissolution of society in the face of a national crisis – and that thematic intent separates it from most exploitation films.

Specifically, Romero gives us a distinct racial allegory here. This is truly commendable – a Black man named Ben is our protagonist, at the height of the Civil Rights movement, and Romero lets Ben’s nobility and righteous fury shine through in every frame.

And the ending speaks for itself: Even after triumphing over the dead, our hero is killed by the living when he is mistaken for “one of them.”

Or was it a mistake?

At any rate, to say that Night of the Living Dead was subversive is certainly an understatement. And Romero carried on his incisive commentary about how humans are the true monsters of the world with five more Living Dead movies spread out over the decades:

Dawn of the Dead – which many consider to be the best of the series - saw Romero take on consumerism; zombies instinctively finding solace in a mall because their collective subconscious drove them to “shop” is the height of satire in so many ways.

Day of the Dead was an indictment of our failed institutions, especially the military.

Land of the Dead built off the seeds of tribalism that were planted in the first film and became a full-on screed against class warfare.

Diary of the Dead tackled the ghoulishness of the media, as well as our ghoulish obsession with the social media spotlight.

Survival of the Dead took the series’ tribalism critiques to its zenith by exploring how we are our own worst enemy; namely, how human beings will never be able to get past our petty feuds and work together for our mutual survival, even during the end of the world.

When you lay it all out like that, it couldn’t be clearer: Every zombie tale that came out after Night of the Living Dead owes everything to George Romero, who was years ahead of his time.

The morality plays, character archetypes, and grim iconography we see in all of these things started with Romero. And as a result of that winning template, it’s pretty clear that zombies have become the most durable monsters of them all.

They’re literally everywhere – on TV with The Walking Dead and The Last of Us, in pull-no-punches thrillers like 28 Days Later and Train to Busan, and in horror comedies like Zombieland and Warm Bodies.

And while many of those stories have carried on Romero’s allegorical commentary approach, I believe that the overarching popularity of zombies stems from something that reaches deeper.

Namely, because the guardrails of the Hays Code were gone, Romero was able to tap into a much more intimate part of our psyches in 1968, which in my view was best captured by that scene in Night of the Living Dead with the little zombie girl:

The primal, terrifying concept that someone you love can be taken over and transformed by something dark and evil.

In later years, the idea of “found footage” – a conceit that Romero himself implemented in Diary of the Dead - took that idea to an even more intimate level. After all, everyone is walking around with cameras in their pockets at all times; how would we even begin to cope with capturing something monstrous happening to our loved ones?

The found footage boom was ushered in by The Blair Witch Project in 1999, and to this day, it remains the best-marketed movie of all time. It literally sold itself on that primal intimacy - on the fact that it was “real” - complete with a website “documenting” many of the events and folklore that led up to the footage we see in the film. And even if we knew in our hearts there was no way it could be real, the very idea that it simply felt real is what mattered.

Case in point: One of the film’s scariest centerpieces amounted to nothing more than someone rustling a tent around while the people inside were panicking as if they were being attacked. And it worked because we have all been inside a tent just like that at a sleepover as our friends tried to scare us. Again, we viscerally relate to it, so it affects us… even if it’s only on a pure theme-park-ride level.

The third act in particular, which culminates in one of the most indelible horror images ever, was just so well done. It was downright electric sitting in that audience for those last ten minutes; hands down, the best theatrical horror experience of my life.

Because of the runaway success of Blair Witch Project - which of course meant there were many pale imitators - the found footage thing was already starting to feel like a gimmick by the time Paranormal Activity came out in 2007. But like that seminal horror film before it, PA makes very effective use of said gimmick by exploiting two very relatable fears: that of an unstoppable, invisible presence invading your home, and that of said presence targeting a loved one.

Just like every time we hear the shark's theme in Jaws, our hearts beat faster here every time it cuts back to that static bedroom shot. And some very chilling things do indeed happen in those bedroom scenes (what makes it even more realistic is that it is always one long shot; there are no cutaways).

Most importantly of all, this gutsy little flick once again illustrates that silence, waiting, and the power of imagination can be more entertaining and intense than “in your face” buckets of gore. Val Lewton would be proud.

That kind of visceral intimacy certainly explains the appeal of ghost stories as well, which are another indelible staple of the horror genre.

Whether it’s a romantic thriller like Ghost or a family-friendly fantasy like Casper, ghost stories often center around the concept of unfinished business - the idea of making peace with a loved one so we can let go and move on. And this in turn affects us deeply because we all want closure of some kind in our lives.

This idea was taken to perhaps its best iteration by writer-director M. Night Shyamalan in The Sixth Sense (1999), which deftly balanced its scares with its emotions. Funny enough, failing to capture that second aspect is why so many of its subsequent “twist ending” imitators fell short (excluding The Others, which is another exemplary ghost story).

In fact, for me, the scene in the car where young Cole comes to an emotional breakthrough with his mother after relaying a message from his late grandmother is just as powerful as ghostly Malcolm’s third-act epiphany. In the end, there’s nothing more uplifting than being seen – both literally and figuratively, in the case of both of our endearing leads.

Undoubtedly, because of the themes and feelings it explored, The Sixth Sense became only the fourth horror film in history to be nominated for Best Picture. And that brings me to the first one...

The Exorcist (1973)

A Dracula story

Ironically, tons and tons of controversial media buzz helped catapult The Exorcist into the stratosphere. It was free marketing at its best.

Despite poor initial reviews - which mostly seemed to be coming from snobby critics who were hating on the genre overall rather than on the individual film itself - the movie became a sensation because of its gruesome content, its purported “true story” roots, the Vietnam-era anxiety in the zeitgeist over real-life horrors, and the attacks from the religious right.

It was absolutely a movie of its time. But it is also timeless, as history has shown us.

And the reason this film is so iconic is because of the naturalistic approach director William Friedkin and his team brought to the story - it feels like the most "emotionally realistic" depiction of what an exorcism might be.

And that is why it has so often been imitated.

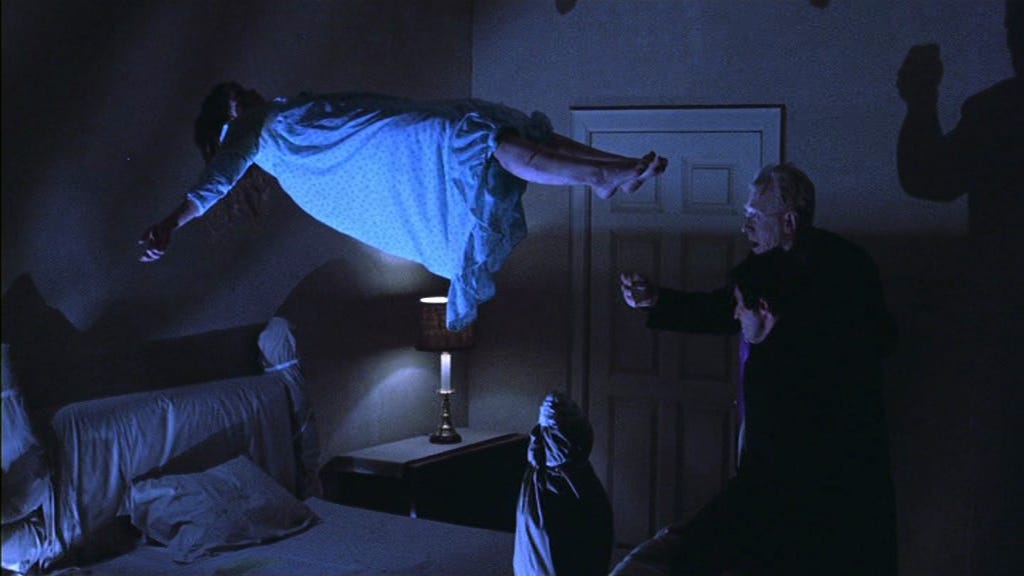

Consider every possession movie made since The Exorcist. A priest always loudly recites Bible verses in Latin. The victim always speaks in a distorted voice, levitates off the bed, and contorts their body. Repeat.

To my mind, it says a lot about the accomplishments of Friedkin and company that pretty much every subsequent film involving demonic possession hasn't evolved past what they did.

That's the sign of a true landmark film, in any genre.

So, what makes The Exorcist so scary?

Well, again, the core idea of the film - that someone you love can be taken over and changed by something dark and evil – is utterly terrifying to imagine. And the fact that this entity knows your deepest fears and will try to exploit them - while forcing you to potentially harm your loved one as you try to save them - drives the concept way too close to home.

And once again, I must credit the naturalistic execution here, since the film’s core premise would be empty without it.

Specifically, the ways in which Friedkin depicts the psychological aspects of the exorcism itself – e.g., how the demon makes Father Karras “see” his dead mother, which directly ties into his crisis of faith – are even more unsettling to me now than when I first saw the film. It is simply harrowing, and it wears us down as it does Karras.

(Actually, the movie as a whole makes me feel more uneasy now, likely because I understand what it was going for more.)

The lack of a score, the layered sound design, Owen Roizman’s shadowy cinematography, Dick Smith’s eerie makeup, the way you can see the temperature get colder in the room, and especially the creaky whisper of Regan’s possessed voice… the film is a masterclass of psychologically unsettling execution.

Another crucial way in which psychology is used as a “fear weapon” here is how the notion of childhood innocence is thwarted at every turn.

Regan, once a sweet little girl, speaks like a warped abomination when possessed, cusses like you’ve never heard, and even masturbates with a crucifix. This last image is especially perverse, as the film depicts a once-pure child committing a staggeringly sacrilegious act using a heretofore untouchable religious symbol.

Again, just perfectly off-putting, psychologically-taxing execution.

And that last aspect is exactly what tips the film over the edge; the more personal the threat, the deeper the fear.

Friedkin and author/screenwriter William Peter Blatty, like George Romero before them, knew that child endangerment would really get us. To this day, I still find the long sequences of the priests stuck in that room with the demon as it batters the poor child it has essentially taken prisoner to be utterly draining and suspenseful. And it’s precisely because Friedkin and Blatty spent so much time making us care about Regan before the terror started.

With that in mind, part of The Exorcist’s legacy is a slew of “scary kid” movies and a slew of “devil” movies, which have become horror subgenres unto themselves.

Before 1973, the closest we had was Rosemary’s Baby in 1968, which sort of combined both arenas.

But that film of course was about a different kind of intimacy, one that revolved around female autonomy and the pressures of motherhood in conflict with the oppressive patriarchy. (Great Sixth Sense-like ending too!)

In truth, "scary kid" films tend to be my least favorite type of horror movies, and it almost always boils down to how the scary kid in question is directed - having your child actor mug for the camera with a furrowed brow like he knows he is supposed to be evil is a good way to derail any chance of empathy. But Exorcist shows us how to handle kids in horror effectively:

Don’t ever let things get too silly by making the kid overly omniscient or overly snarky - subtlety and silence go a long way in making them seem like viable threats.

Don’t pull your punches or shy away from putting the kid in peril - show us that this is as dangerous for them as it is for their loved ones.

Don’t be afraid to tap into the fears of kids as well as those of adults – after all, from an innocent child’s perspective, it will look like their parents are suddenly turning on them too as they are pulled toward an unknowable evil they can’t comprehend.

Two modern “scary kid” films that I felt did quite a good job of conveying all this are The Children (2008) and The Innocents (2021). Seek them out! But I believe that the ultimate scary kid movie is The Omen (1976) because it aptly embodies that third technique mentioned above.

Near the end of the film, Gregory Peck’s Robert Thorn goes to kill the Antichrist… but the little boy in his arms starts crying and calls out his name. Thorn stops short because, at that moment, he is holding his beloved son, not the son of the Devil, who doesn’t understand what is happening.

The helplessness, fear, and tragedy are palpable in this heartbreaking scene; it feels like the apex of director Richard Donner’s operatic intent for the story, complete with ethereal cinematography and a haunting score that wholeheartedly support this aesthetic.

Again, it’s all about how a story is told.

I first saw The Exorcist when I was a literal Catholic schoolboy, and it scared me so much that I slept with a rosary that night! Nowadays, as I stated before, I find the film to be even more effective, despite no longer being in any way religious.

And to me, this means that what matters most when it comes to horror is execution (in case I haven’t said it enough). The ideas behind the horror, the ways in which those ideas are dramatized, and how the characters process it all must resonate with us in order for us to truly be affected.

And this means that in order for a horror filmmaker to be successful, they must possess (heh) the intuitive sense of the kinds of imagery that a large swath of people would find instinctively scary, and then execute it in such a way that makes your mind go, "Oh, man, if I was seeing this in real life, I would be crippled with fear."

It is no small feat, that’s for sure. But ultimately, I believe this is the sign of a truly powerful film - when you can scare even the people who don't have a real-life emotional connection to your subject matter, then you have tapped into something primeval and universal.

Something intimate.