Horror thrives off the mysterious and the eerie – the unknown.

And the way we cope with the unknown, in both real life and in fiction, is by imparting rules onto the mystery in order to give ourselves a semblance of power over it. (The framework of religion.)

Consider 1941’s The Wolf Man, which adheres to some easily understandable mythological rules - Larry Talbot only transforms into a werewolf under a full moon, he can only be killed with a silver bullet, etc.

Creating these rules grants us the cathartic process of fearing the Wolf Man* because he breaks our known laws of reality, but simultaneously, it allows us to defeat him.

*Since Larry Talbot can’t help what he has become and tries to stop it, I would classify The Wolf Man as a Frankenstein story, as per the last essay. And just for fun, I’ll also be classifying each “featured” film going forward in this series.

In other words, since we can’t control much of anything in real life, we devise means of surviving horrific scenarios in our stories as a means of control. It’s a psychological shield of compensation, if you will.

That’s why getting inside our heads and breaking our shields is the primary goal of horror filmmakers; all things considered, they have only gotten better at wielding the psychological tools to do so.

And their toolkit was immortalized by the unsung hero of psychological horror.

Val Lewton was a film producer and screenwriter best known for a string of low-budget horror films he produced for RKO Pictures in the 1940s. Lewton brought a sense of sophistication to his films; complex themes and layered characters are two of his hallmarks. But the primary reason the films he produced have become so well-regarded is because he had to get creative.

Namely, Lewton had to deal with three major restrictions during his time as the head of the Horror Department at RKO:

The first was a list of pre-selected titles from the RKO executives… which meant he had to craft a film to fit each title, no matter what, as opposed to the other way around.

The second was budget restrictions, seeing as RKO relied on low-cost “B movies” to keep them profitable.

And the third was the Hays Code, a very restrictive church-and-state censorship mandate that limited what could be depicted onscreen.

All of which were very suffocating from a horror standpoint.

The way Lewton got around these restrictions was by relying on Freudian psychological triggers, suggestive camerawork, atmospheric sound effects, the tension of the slow build, and startling “cat scares” (also known as jump scares) rather than showing actual deaths and gore onscreen.

While this did help keep the costs and the violence down, it probably would’ve been Lewton’s approach anyway, as he was said to be a proponent of “less is more.”

He was big on the idea that the unknown is way more frightening than the known.

A modern horror movie that feels very Lewton-inspired is 2016’s Under the Shadow. Set during the Iran-Iraq war, the film centers on a mother who fears the undetonated missile that struck her apartment building might have unleashed malevolent spirits who are trying to possess her daughter.

The film deals with the kind of complex psychological themes that are trademarks of Lewton’s work – i.e., how to survive as a woman and a mother in a male-dominated, war-torn world – and is full of slow-burn scares.

One scene that perfectly illustrates the latter occurs when the mother, Shideh, first starts getting the feeling that something isn’t right.

Conveyed completely by sound effects and unsettling camerawork, Shideh gets out of bed in the middle of the night to find the source of a loud cat-like howl. And just as she approaches the window, something flashes by and makes a loud noise – but it’s only a sheet hanging to dry outside, flapping in the wind.

Lewton would be quite proud of that auditory cat scare… and since this is the second time I’ve used that term, we might as well define it!

According to TV Tropes, a cat scare is “a strong buildup of high tension, followed by a fright that turns out to be something harmless (say, a startled cat) to release that tension.” This technique stemmed from Val Lewton’s aforementioned need to get creative with his scares – after all, a well-executed piece of misdirection is the perfect way to mess with people’s heads.

Funny enough, the term was coined because of a specific scene in Val Lewton’s most famous movie… which didn’t even involve a cat.

Cat People (1942)

A Frankenstein story

The most fascinating aspect of this landmark film is how it has elicited so many different reads over time. And this in turn is a true testament to the profundity that Val Lewton brought to his work.

My primary read of Cat People is that it is a cautionary tale about self-control versus repression.

Our protagonist Irena is saddled with a deep guilt that stems from her people’s bloody history of witchcraft and murder, as well as from some unknown events in her past - she most likely has innocent blood on her hands.

Since Irena has always been afraid of what she sees as an inherited darkness - a jealous rage that transforms her into a murderous jungle cat - she has repressed this curse instead of trying to take agency and control it.

We especially see this behavior in the scenes where Irena is talked into seeking help from psychiatrist Dr. Louis Judd, only to run away from said help.

The film also uses Oliver, Irena’s newlywed husband, to illustrate its thematic commentary on self-control. When talking to Alice, his assistant, Oliver implies that he married Irena not because he “knew” her, but because he was “in lust” with her – in other words, he had no self-control. Then, at the end of the film, Irena seems to give in to the darkness instead of trying to dominate it, and she takes the only way out she can see, which is to end it all.

This read of the movie says that we must learn to control our desires and darker impulses because if we repress them or run away from them, we will only end up hurting ourselves and others.

On the other hand, an alternate read might be that Cat People is about the dangers of “mansplaining.” I use that term in jest, but in truth, the male characters of Cat People try to manipulate Irena – they try to get her to be what they want her to be - instead of truly trying to listen to her and help her.

It certainly doesn’t help matters that as soon as things get complicated with Irena, Oliver wants to bail. He even laments to Alice about how things have always been “simple” for him. Alice quickly tells Oliver that she is uncomplicated, thus confirming that she will be exactly what he wants her to be.

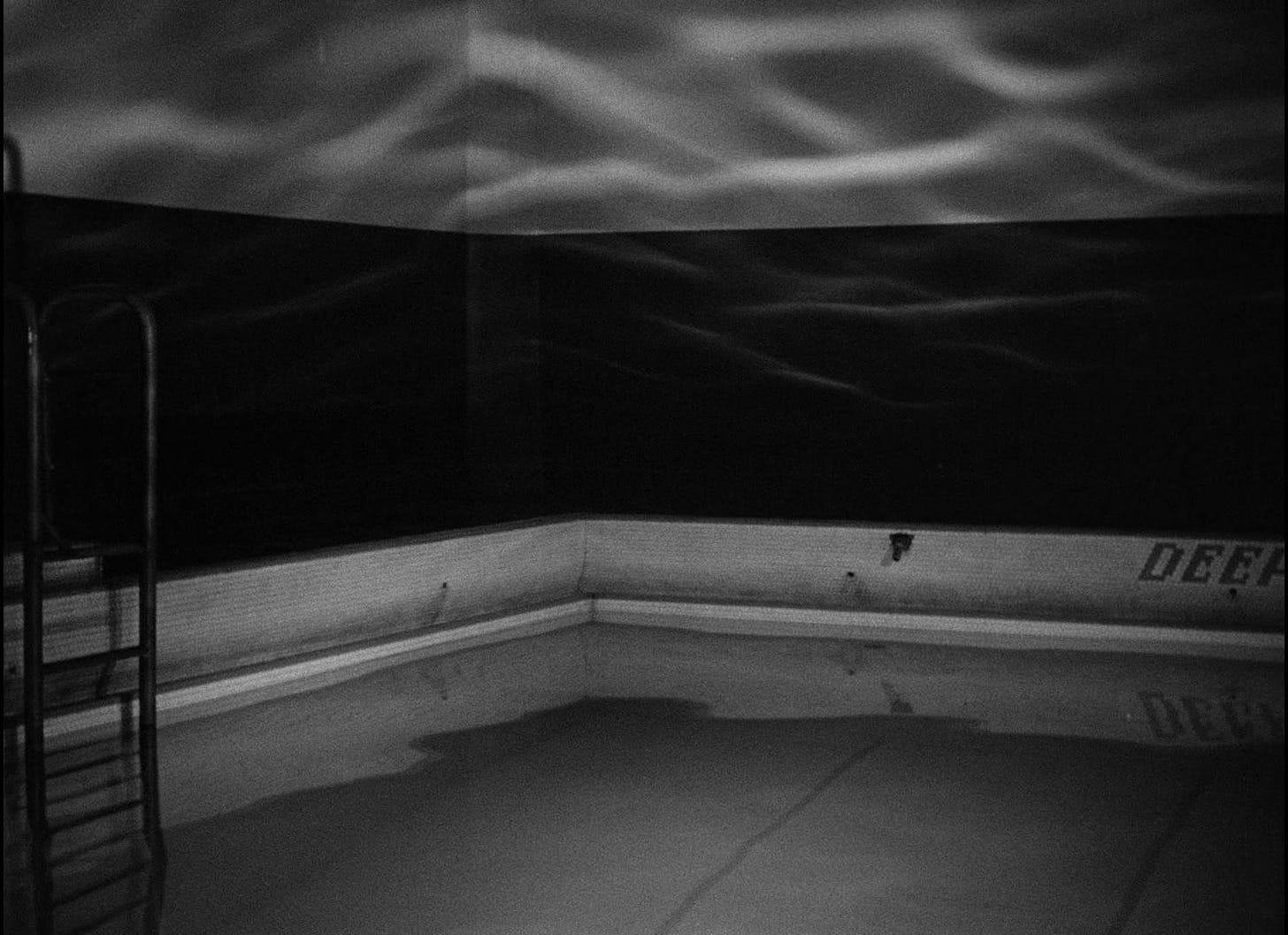

This only serves to inflame Irena’s curse, resulting in some incredibly well-orchestrated “stalking” scenes that were way ahead of their time from a suspense filmmaking standpoint, including a powerhouse sequence set in a swimming pool.

“Less is more” horror films like Jaws owe a lot to Cat People, that’s for sure!

And then there’s Dr. Judd, who talks down to Irena with utter condescension about her condition, trying to easily explain it away as being “just in her head.” Even worse, Dr. Judd tries to take advantage of Irena, and that results in his comeuppance.

One man tried to abandon Irena, and the other tried to abuse her. This leads Irena to finally embrace what she is and seize control of her own destiny.

To some degree, one might say Irena was being selfless in the end, taking her own life because she knew that her incurable curse would continue to compel her to take innocent lives.

At any rate, it’s clear that Cat People has multiple layers that can elicit multiple meanings, which makes it a truly important horror film. And those layers stem from the fact that Cat People functions as an allegory, which is another key psychological storytelling tool of horror filmmakers.

As a refresher, an allegory – a term we touched upon in our last essay, concerning vampires – is a story in which characters and events are used as symbols to teach us crucial lessons about the human condition. For example, the Icarus story allegorizes the dangers of human arrogance, and the novel Lord of the Flies allegorizes what can happen when humankind’s barbaric nature goes unchecked.

Horror-wise, as we jump-scared out of the 1940s and dropped into the 1950s, allegory became big – sometimes quite literally. (The ultimate hey-o!)

The “Monster Movies” of the 1950s successfully tapped into the paranoid zeitgeist of the time, which was brought about by the advent of the atomic bomb.

Panic shelters were being prepared in basements, and preachers were sermonizing about the morality of shooting one’s “radiation-soaked” neighbor. As such, the monsters of these movies symbolized the horror of bringing the world to the brink of extinction, and the burden of having to deal with the consequences.

Now, there has been some debate about whether these films should be classified as science fiction instead of horror. My view is, while they might have sci-fi trappings on the surface, they are horror movies at their core because of tone and theme.

Sci-fi often taps into our intellect, while horror taps into our emotions. Sci-fi usually revolves around vaguely plausible scenarios and technology, while horror usually revolves around fantastical and supernatural scenarios that could never happen in real life.

In short, the Gothic horror films of the past were carefully crafted manifestations of our primal fears, and the ‘50s Monster Movies simply carried that ethos over into modern “scientific” settings because that’s what those particular stories were about: the horrors of science.

As a basis of further comparison, a film like 1933’s King Kong does not fit in with those 1950s Monster Movies because of what Kong himself represents.

In those ‘50s films, the threat was often something we didn’t understand, and thus it had to be destroyed.

Kong on the other hand represents our primitive past, one in which we acted on animal instinct. This means we can relate to him on some level.

Kong’s home was invaded, he was taken from it, and he was attacked; he was just defending himself. So we project ourselves onto Kong and give him a soul - thus, he symbolizes remorse, guilt, and nostalgia.

Ultimately, we understand Kong, which makes him more of a victim than a monster… and that is a Frankenstein story if there ever was one.

Scholars point to Howard Hawks’ The Thing from Another World (1951) as the originator of the 1950s Monster Movies.

The Thing features a group of scientists and military men who discover an unknown alien abomination in the Arctic and must use their military and scientific knowledge to combat it.

This establishes the core theme of “only science can save us,” which became an iconic underpinning of the subgenre. And perhaps most essentially, The Thing ends with an uneasy sense of, “We won this time, but next time...?” And such ambiguous endings would also come to define this subgenre.

Here are a few other famous Monster Movie allegories of the time:

The War of the Worlds (1953) allegorizes the dangers of imperialism, with hostile Martians ironically standing in for us humans. The film seems to argue that in trying to conquer the indigenous civilizations of our planet, we will only succumb to our hubris.

This is symbolized by the fact that the aliens, overconfident in their power, are brought down by failing to immunize themselves against common bacteria.

Godzilla and Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954) allegorize the dangers of crossing the boundaries of science and nature.

Both films can be read as indictments of the United States, given our nation’s history of encroaching into volatile existential territory that we have no business dwelling in – the fallout of nuclear weapons is represented in the former, and the destruction of the natural world is represented in the latter.

Them! (1954) portrays scientists as calm, fatherly authority figures who know exactly how to defeat the unprecedented threat of giant mutant ants, along with the aid of idealized soldiers who are depicted as manly and heroic.

In fact, collectively, they both represent “THE U.S. GOVERNMENT!” which will use all its military and scientific might to defeat all the chaos and defend us from all the threats.

And this notion was a running theme throughout most 1950s Monster Movies as well: “Trust your institutions because we can’t trust ourselves.”

Hmm, what a perfect segue to the most prescient allegorical Monster Movie of the 1950s…

Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956)

A Dracula story

Invasion of the Body Snatchers presents protagonist Miles Bennell’s town of Santa Mira as an “idealized” version of what many people in the 1950s wanted the U.S. to be. That is, a country full of hardworking, honest, loyal civilians helping their neighbors and living in safe neighborhoods with their nuclear families.

This worldview forged its way into our society after World War II, which had been an incredibly tumultuous period for the country. As such, people wanted a return to peace, and so the town of Santa Mira represents “normalcy.”

Hence, in the context of what this aspirational utopia signifies, the invasive alien pods that transform into emotionless, subservient doppelgangers of Santa Mira’s residents symbolize the dangers of normalcy – or rather, what a government-mandated idea of normalcy “should” be.

These “body snatchers” represent what happens when you give yourself over to the agreed-upon norms of society (marriage and the white picket fence) even if you don’t want them, while keeping your head down and never questioning authority even when it’s called for.

In the end, the pods are metaphors for our worst fears - the eradication of our identity, our agency, our independence, our free will, and the one thing that truly belongs to us, our soul.

Because of these factors, many scholars read Invasion of the Body Snatchers as an allegory for the Red Scare of the 1950s, which led to McCarthyism - the government-led “purge” of suspected communists - overtaking society.

While the filmmakers denied such outright intentions, the film definitely reads as a commentary on the evils of complacency and conformity, which go hand in hand with McCarthyism.

That said, whether the Red Scare was the filmmakers’ outright inspiration or not, the issue certainly was in the zeitgeist at the time – hell, it was the zeitgeist. So there’s little doubt that such commentary couldn’t help but seep into the film.

With that in mind, the main reason we can buy into the Red Scare angle is because of the way the film masterfully channels that universal feeling of paranoia, i.e. “Everyone is out to get me.” And we can see this primarily in the way the film handles figures of authority.

For starters, it seems as if authority figures of all stripes may have been the first ones to fall under the pods’ sway. This is evidenced in the way the police constantly try to divert Miles’ search for the truth, and how the soldiers near the end of the film enact what surely must have been a months-in-the-planning plot to disperse the pods nationwide.

In particular, the (compromised) police implicitly send a message to Miles that he must behave and fit in… or else.

Consequently, it’s in these moments that the persecutional, witch-hunt nature of McCarthyism creeps in, intentional or not.

It is also interesting to consider how Miles himself is a figure of authority, a doctor, yet the other authority figures in town don’t heed his warnings because he is not like them - he thinks and acts differently, he questions his surroundings, he isn’t married.

In other words, Miles has not conformed.

At one point, another authority figure, a psychiatrist, talks down to Miles in a condescending yet patient way, conveying that creepy “everything is all right, ignore the truth, we are in charge, blindly trust our overlords” vibe that many have come to negatively associate with authoritarian regimes.

Later, when Miles tries to call for help, the phone operator repeatedly says that no one is available. And this telling moment only underlines the thematic skepticism that was present in the earlier psychiatrist scene:

“When it comes down to it, maybe you can’t trust your institutions after all.”

Ironically, director Don Siegel had to contend with his own kind of antagonistic institution in the form of the studio, who snatched away the identity of his film.

Along with removing the dark humor that had been woven into the original edit, the executives at Allied Artists changed Siegel’s vision of Body Snatchers by making him add a framing device.

The film now begins and ends at a hospital, wherein Miles warns several “trustworthy” authority figures about the pods. Once the doctor there hears a corroborative story about the pods from a truck driver, he believes Miles and immediately calls the FBI to save the day.

This studio-mandated change seemed to come from the notion of not wanting to criticize our government in that era of 1950s idealism. But the true irony is that this mandate mirrors the suppressive “let’s not rock the boat” aspect of the film that the pods themselves embodied.

Originally, the film ended with Miles’ nightmarish scramble down the highway as he screamed, “You’re next!” right into the camera. Given the feeling of paranoia this scene aptly taps into, as well as its novel lack of closure and its subversive “don’t trust authority figures” vibe, the director’s ending is clearly a better fit for the nature of the story.

On the other hand, I tend to agree with the read that Siegel just might have smuggled one last bit of paranoid subversion into the studio ending too.

After Miles’ story is finally believed, the camera lingers on his face while the authority figures surrounding him make phone calls to other authority figures, on their way to saving the day.

Miles breathes a sigh of relief and sags against the wall; however, his expression doesn’t read as one of happiness and triumph, but one of exhaustion and surrender.

In the end, our stalwart hero seems to give in to his overlords… which is inescapable if they are indeed always out to get you.

And who knows what they’re gonna do to us next?

For me, the reason that Invasion of the Body Snatchers feels timeless beyond its Red Scare roots is because it champions nonconformity, and that can be applied to any decade and any genre. We’ve had three direct remakes, in fact - one in 1978, one in 1993, and one in 2007.

There have also been many similar films like The Puppet Masters, They Live, The Faculty, The World’s End, and Get Out, which are all variations of the film’s core conceit. (I’m sure someone is already planning yet another version for tomorrow’s politically heated climate.)

And that brings us to the most famous allegorical alien body genre horror film of them all, which is simultaneously Body Snatchers adjacent and similar to Cat People in its exploration of women’s issues.

It even has a famous movie-star cat…

Alien (1979)

A Dracula Story

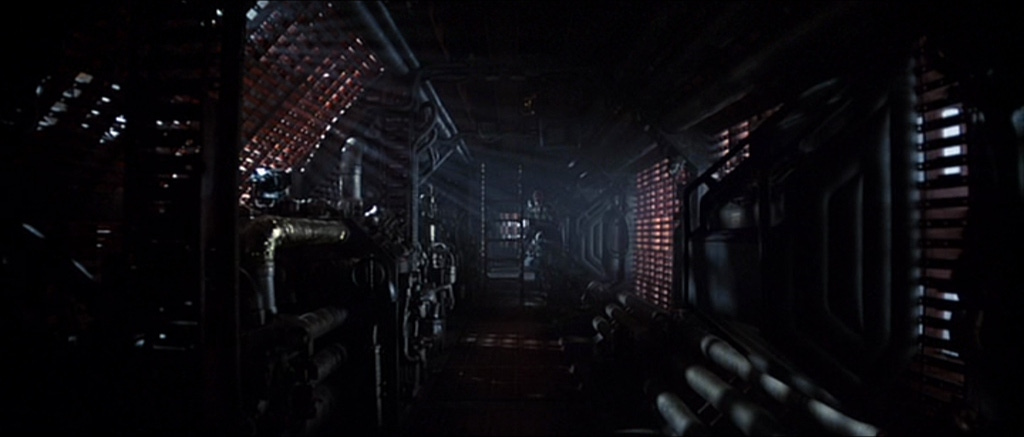

In what many would deem his seminal work, director Ridley Scott and his team crafted a Freudian fever dream featuring distinct psychosexual imagery and production design, instilling a palpable sense of danger into every frame.

In short, many see Alien as a rape parable, which is a very specific kind of allegory that deals with the persecution of the historically marginalized.

The film’s titular creature is fueled by an instinctual need to violate, forcefully implanting its seed by thrusting its phallic weapon into unwitting bodies and emitting a lethal bodily fluid - a truly terrifying depiction of how rape survivors might symbolically perceive their attackers.

Furthermore, Alien explores how gender dynamics are upended by rape.

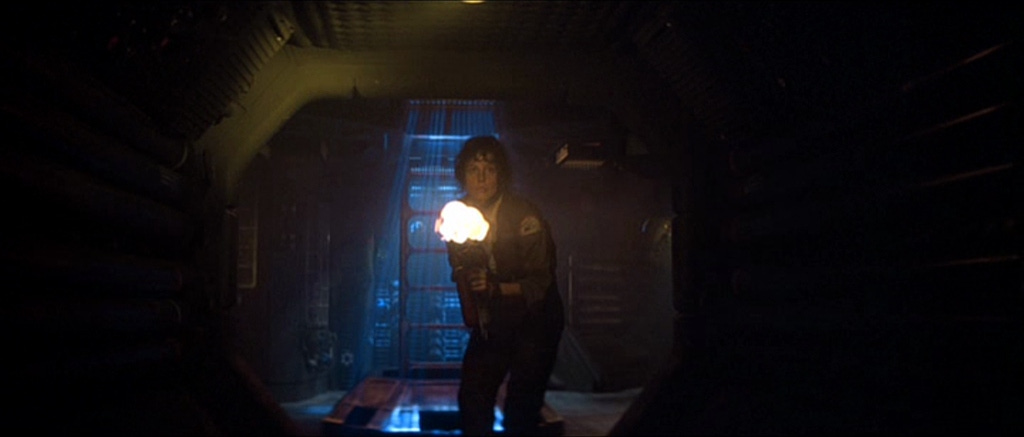

Once the “rapist” strikes by attaching itself to Executive Officer Kane’s face, Science Officer Ash - the embodiment of a very distinct, masculine abuse of power - doesn’t heed the authority of our female protagonist Ripley. Instead, Ash allows the crew to bring Kane and his aggressor onboard, endangering them all.

And because Ripley is not “believed,” everyone else is killed.

As the film progresses and Ripley struggles to survive, the spaceship set design seems to become more Expressionistic, reflecting Ripley’s agitated psychological state.

Soaking in distrust and isolation from every dimly lit claustrophobic corridor, we follow Ripley as she fights her way through this nightmare in space. She even finds herself in a physical confrontation with Ash, who tries to choke her with a phallic object.

This opens up a whole new can of Freudian worms, seeing as the character who comes closest to violating Ripley is not the villain, but someone she knows. Another facet that’s unfortunately true to life.

Ash is eventually stopped by another crew member, but the important takeaway is that he was hellbent on bringing the creature back alive, as per his orders from their employers – i.e., a company was protecting the attacker over the victims.

Again, sadly, true to life.

Later, after seemingly vanquishing the alien and finally feeling safe, Ripley disrobes down to her (metaphorical) soul. This is when Ripley is at her most vulnerable, so of course this is when she is promptly attacked.

In the end, Ripley doesn’t let the vicious alien infest her, but she is forced to fight it alone. As such, the overarching message of Alien is that women must contend with sexual violence in a way most men will never understand. Given the reality many women are facing nowadays in our world, that message seems timelier than ever.

And that is the true power of the horror allegory: It is immortal.